Views and Reviews

by Alidë Kohlhaas

At this time of year, thoughts turn to Christmas trees and the gifts to be placed beneath them for loved ones. Let me begin with the tree. For the 12th season, The Gardiner Museum of Ceramic Art has on display a baker’s dozen of designer Christmas trees. They are the painstaking work of Toronto designers, some of whom have made trees since the show’s inception. Each year they explore a different theme. This year it is "Art through the Ages." The trees are auctioned off to benefit the museum. In turn, many of these trees then are donated to hospitals and other places where they help to cheer the sick, elderly and needy. They are on display at the Gardiner to December 13.

On the museum’s front stands a 14th tree that is part of the Cavalcade of Lights along Bloor and University Avenues. Wrapped in red translucent material, its exterior is inspired by the artist "Christo". Several years ago he covered the then unrestored Reichstag in Berlin with plastic. At night, white interior lights illuminate this red tree, freeing it from all resemblance to the inspiration.

The tree that greets the visitors in the lobby of the museum is shear playful whimsy. It echoes the wonderful "Miró: Playing with Fire" display of the late Spanish artist, Joan Miró’s pottery on show at the museum until January 7, 2001. This show is another reason to make a trip to the museum.

It is impossible to list all the trees, but each is something to behold. The "Gothic" tree plays a little joke on the viewer. While celebrating the song, The twelve Days of Christmas, it has replaced, in true Gothic style, the partridges with ravens. The "Druid-Celtic" tree is covered in ivy, holly and mistletoe. The "Italian Renaissance" tree features a wide variety of hand made decorations, which speak of the decorative richness of that period. The "Art Deco" tree is covered in shimmering ornaments of silver and topped with what looks like the pinnacle of New York’s Chrysler Building.

Now for something to place under the tree. M. Owen Lee has written the perfect gift for opera lovers, and those who enjoy to solve quizzes, anagrams, etc. Every question, every piece of a puzzle relates to the subject of opera. This reviewer loved it, even though there hasn’t been the time to answer every question or fill in every puzzle. That will happen later! The book is 187 pages (including answers) full of delight. [Father Lee’s Opera Quiz Book, paperback, University of Toronto Press, $18.95]

For someone, who loves a good story, Norman Levine’s "By A Frozen River" is a great gift. Levine captures the essence of Canada as few writers can. He does so with an understated, clean, even spare style, yet amazingly evocative of landscape and space. Born in Ottawa in 1923, he covers a wide period. As an expatriate, living in England, he writes about our world from afar with a far keener sense of home than those writing at home. He also gives us a peek of his England, one that rings terribly true, as this reviewer can attest from experience. Each story, generally unrelated to the next, is a glimpse into our landscape. Although told in the first person singular, and no doubt drawn from the writer’s own experiences, these tales must not be taken as biographical. Instead, they are encounters of one kind or another into which the reader is drawn irresistibly. [By A Frozen River, Key Porter, paperback, 311 pages, $21.95]

The Toronto Symphony Orchestra gave us music inspired by William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Felix Mendelssohn, of course, wrote the most famous incidental music to the comedy, and the TSO played the overture. It’s a lovely work. Mendelssohn understood the Bard’s comedy, its humour and its reflections, and his music takes one on a wondrous journey with Puck, Oberon, Titiana and all their fairies, as well as lets us laugh with and at Bottom and his raucous fellows. So, one wonders, why the conductor chose to rush his players through this piece as if he wanted to get rid of it. They, in response, gave a disciplined, but perfunctory performance of the work.

Conductor Jukka-Pekka Saraste, set to leave his TSO post next June, then showed far greater enthusiasm for the next work on the same theme, written by contemporary German composer, Hans Werner Henze. Saraste introduced the piece as if to put the audience at ease. To which one likes to respond that if a musical work needs a verbal explanation, it has failed. Called Symphony No. 8, the Boston Symphony Orchestra commissioned it in 1993. Most of Henze’s works have a political nature. This shows even in the 8th, and one quickly had to disassociate the piece from A Midsummer Night’s Dream to come to some appreciation of it. For, in truth, it did not recall a dream, but a nightmare.

The final work of the evening was Rachmaninoff’s Piano

Concerto No. 2, with no allusion to Shakespeare. Both the TSO and pianist

Krystian Zimerman excelled in its performance. The orchestra sounded lush,

and Zimerman endeared himself doubly for eschewing all pianistic

histrionics. He and Saraste appeared to be in complete harmony in their

interpretation of the piece.

At the St. Lawrence Centre the Canadian Stage Company is presenting "The Weir" by Irish playwright Conor McPherson. It’s a play full of dark Irish humour, well acted and directed. The setting is a small-town-bar in west Ireland, and the action takes place in a single night in one act. Here local bachelors Jack (Barry McGregor), Jim (Robert Persichini) and barkeeper Brendan (Oliver Becker) spin tales to show off to a newcomer, Valerie (Ann Baggley). She is being squired by Finbar, a local man of means, the only married man in this ensemble of bar flies. As the spirits flow freely and loosen restraints, they reveal that Valerie, too, has a tale to tell, one that is haunting and sad. Like Norman Levine in his stories, so McPherson knows how to draw an audience into lives he portrays with understated but descriptive prose.

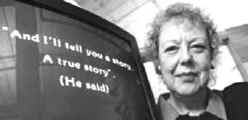

Toronto’s

Goethe Institute is the scene of an installation by Canadian artist Vera

Frenkel. This mixed media work employs six short videos, wall-sized

photographs and an Internet site to create a fictional documentary about a

group of artists in Linz setting out to track down art treasures that

vanished from the salt mines at Altaussee at the close of WWII.

Toronto’s

Goethe Institute is the scene of an installation by Canadian artist Vera

Frenkel. This mixed media work employs six short videos, wall-sized

photographs and an Internet site to create a fictional documentary about a

group of artists in Linz setting out to track down art treasures that

vanished from the salt mines at Altaussee at the close of WWII.

Like the characters in McPherson’s play, these artists meet in a bar. Called the Transit Bar, a place Frenkel first created for an installation at the Kassel Documenta 9 in 1992, she has now moved it to Linz. Interestingly, some artists in Linz are now doing exactly what Frenkel imagined. "Bodies Missing" first opened at the Offenes Kulturhaus in Linz in 1994, and has since been shown in Tokyo, Kyoto and Sapporo.

The voices on the video sometimes speak German, sometimes English, but even for a non-German speaker, the videos are easy to follow. Among the sound devices Frenkel used is the children’s rhyme Maikäfer Flieg! In an ironic way it works itself into the mind as well as into the idea of the fictional tale. Maikäfer (May bug) Flieg is similar to our Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home! , although two different insects are involved. The first rhyme dates back to the Pomeranian wars in the 17th and 18th centuries, the latter to at least George II’s reign.

Body Missing’s web site is at http://www.yorku.ca/BodyMissing . If you can’t make it to the show, it closes on Dec. 21. then this is an interesting way to explore Ms Frenkel’s ideas.

Comments to: alide@echoworld.com