Views and Reviews

by Alidë Kohlhaas

The story of Henry IV takes place when the real King Henry IV faces insurrection from the Scots, the Welsh, some of his own supporters, and the Bishop of York. Shakespeare, taking artistic license, combined these insurrections into one, when in actual fact they were quelled over several years.

Henry IV, Part I at the Tom Patterson Theatre does what a good Shakespearean production should do, it allows the audience to use its imagination. The set consists of a few boxes and a chair that are rearranged to suit the play’s settings. It is classic in its sparseness and classy in its effect. One very effective tool is a huge cloth map of Britain. The warring factions, with division in mind, walk across it and point at the area they claim.

The costumes are a mixture of old and modern, creating a "silhouette" effect. This mixture is one factor that helped director Scott Wentworth and designer Patrick Clark to create a well-defined production.

Graham Abbey makes a fine transition from the carousing youth, who drinks too much with the likes of Sir John Falstaff to the disciplined Prince of Wales who must lead his troops to win a battle at Shrewsbury to save his father’s crown. Douglas Campbell as Falstaff never lets the jokes get out of hand. He is utterly funny and yet deadly serious when he play-acts the King in an interview with his irresponsible son. This acting exchange between Falstaff and Prince Hal sets the tone for the much darker second part, Falstaff (Henry IV, Part II).

Jonathan Goad’s young Hotspur, the son of Sir Henry Percy, is portrayed with verve. This is a believably wilful, pouting youth, who loves fighting and war over all else and who feels himself superior to Prince Hal. Of course, Shakespeare (and history) taught him otherwise. As the two opposing monarchs, Glendower and Henry IV, Stephen Russell and Benedict Campbell show majesty. The latter uses restrained action to show the conflict within himself and in his realm. Russell achieves grandeur in an impressive wig and a sweeping cloak. In Welsh folklore, Glendower is a mythical hero, a warrior magician, and Russell plays on it.

The fight scene at Shrewsbury is beautifully choreographed. The opposing principals in the battle, Hotspur and Prince Hal, are in full armour. The well-orchestrated chaos around them plays in slow motion to great effect. Henry IV runs until September 29.

Jukka-Pekka Saraste’s farewell concert with the Toronto Symphony Orchestra presented Arnold Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder. His stellar cast consisted of tenor Ben Heppner as Waldemar, soprano Andrea Gruber as Tove, and mezzo-soprano Lilli Paasikivi, tenor Benjamin Butterfield, bass-baritone Gary Relyea, tenor Ernst Haeflinger, The Toronto Mendelssohn Choir, and the Victoria Scholars. The TSO added 40 musicians to get as close as possible to the 150 needed for the score.

The Gurrelieder are a series of 21 songs that tell the story of 12th century Danish King Waldemar the Great, who is said to have fallen in love with a young woman, Tove-Lille (Little Dove). The story became linked with King Waldemar IV (1340-1375)and his wife, Queen Helwig. She supposedly had the young woman killed. Waldemar, after cursing God for having allowed this to happen, was doomed to ride through the night with his men even after his death. Schoenberg, after reading a German translation of the poem cycle, took 10 years to complete his cantata. It premiered to acclaim in 1911.

What the audience heard on June 14th must have overwhelmed many as the work can overpower the ear and the senses. There were moments of delight, of glory that captured ones emotions with the richness of sound. But this complicated work placed a heavy load on the orchestra. Its members played unhesitatingly, which showed that much rehearsal had taken place. Yet, it also revealed that Saraste had not stood back far enough to hear his musicians, for he failed to rein in their urge to be heard above the large crowd they formed on the Roy Thomson Hall stage. This caused the vocal soloists to vanish under monumental sound at moments of maximum orchestration.

Here is where one envies the listeners of CBC Radio Two’s replay of that night on June 20th. They were able to hear the soloists in Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder, who stood right in front of the recording microphones. Heppner, renowned for singing Waldemar, got the worst of this lack of control of orchestral volume. One sensed his famous high notes but could not hear them. He visibly struggled to get free of the orchestra. Fortunately, he now and then broke through with his golden phrasing and his clear pronunciation.

Gruber also had to struggle to be heard. She thus failed to reveal why orchestra leaders often choose her for the role of Tove. Paasikivi (Wood Dove), Butterfield (Jester Klaus) and Relyea (Peasant) faired far better. Their voices floated freely over the lighter texture of the orchestration in their songs. Haeflinger, 82 this year, stole the audience’s heart. He was splendidly lyrical as the Speaker.

The might of the male voices of the combined choirs survived the orchestral onslaught. And in the final brief song of the Chorus, male and female voice blended to give life to the highly expressive, positive lines of the poem and orchestration. These last moments, beginning with Haeflinger as the Speaker, ended all of the past strain and lack of control. It was, indeed, a glorious finale.

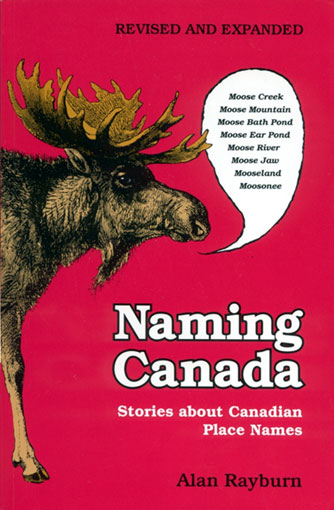

For

those, who like to read about Canadian History, Naming Canada will make good

summer reading. Alan Rayburn has written several books on this subject. The

current Naming Canada is an updated and revised version of a book first

published in 1994. It is easy to read, full of detail, and written with a

fine sense of humour. Rayburn even supplies us with an excellent recipe for

Nanaimo bars. [Naming Canada: Stories about Canadian Place Names, University

of Toronto Press, 360 pages, $24.95 paperback].

For

those, who like to read about Canadian History, Naming Canada will make good

summer reading. Alan Rayburn has written several books on this subject. The

current Naming Canada is an updated and revised version of a book first

published in 1994. It is easy to read, full of detail, and written with a

fine sense of humour. Rayburn even supplies us with an excellent recipe for

Nanaimo bars. [Naming Canada: Stories about Canadian Place Names, University

of Toronto Press, 360 pages, $24.95 paperback].

Comments to: alide@echoworld.com